So, with all the data above plus that extra bit of background about me, I will add a bit more. There is a big problem emerging in global financial markets. A big part of the issue is governments and their habits of borrowing to spend far in excess of their revenues (and in ways that many might argue are “less than wise”).

Like which governments? The US, China, Japan, the UK, and… almost all of them really. But the biggest debtor is the US Treasury (at just under $35 trillion of debt).

As the short-term loans (of less than 5 year duration) come due among the extra $20 trillion of borrowing from the last few years, that is a lot of “demand” for new loans. All of that demand is competing against people who want to borrow money for things like buying homes or for construction projects of new homes.

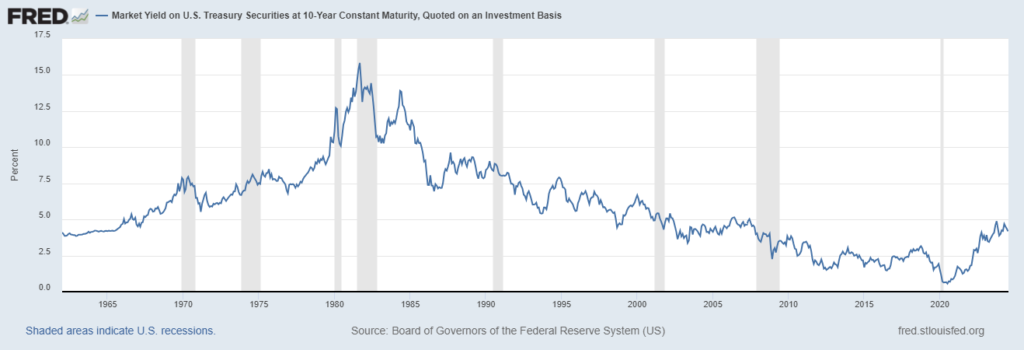

So who is driving up interest rates?

The mass media and public schools may not emphasize the simplicity of the following issue, so it may be a bit of a shock to you. The biggest single influencer of interest rates in the US is not the Federal Reserve, but the US Congress (and the budgets signed by Presidents like Trump and Biden that authorize trillions of dollars of deficit spending). Congress authorizes the US Treasury to borrow aggressively, so the bureaucrats at the Treasury go out into the open market to seek trillions of dollars of loans.

From who? From whoever. Anyone can lend money to the US Treasury. That is also known as buying a bond or a “savings bond.”

(My grandparents used to buy them for my birthdays going back to when I was a toddler. Here’s a link to do it online for as little of $25: https://www.treasurydirect.gov/savings-bonds/buy-a-bond/ )

So, now let’s get back to the US Treasury going out to try to borrow a few trillion dollars from whoever has some extra cash for that. What if the Treasury is trying to borrow $2 billion tomorrow, but the lenders available only want to lend $1 billion at yesterday interest rate? Then the US Treasury raises the rate that they offer in order to reach their $2 billion need.

(By the way, I did not pick $2 billion per day accidentally. Currently, just to pay interest on the trillions of dollars of US government debt, it costs the US government MORE than $2 billion each calendar day – indeed closer to $3.2 billion for every weekday. Again, that is just to pay the interest… not even touching the principal amount owed.)

So the beggars… I mean the bureaucrats at the US Treasury go out into the open market to attract borrowers. And who is the US Treasury competing against in attempting to attract loans? It’s only every other government on the planet, plus every corporation, plus every individual borrower or loan applicant.

$3.2 billion each weekday is enough to cover the interest at current rates. However, those rates get driven up by… the US Treasury failing to attract long-term lenders and being forced to take short-term loans (like 6 month or 2 years) and then after that, the entire principal must be borrowed again.

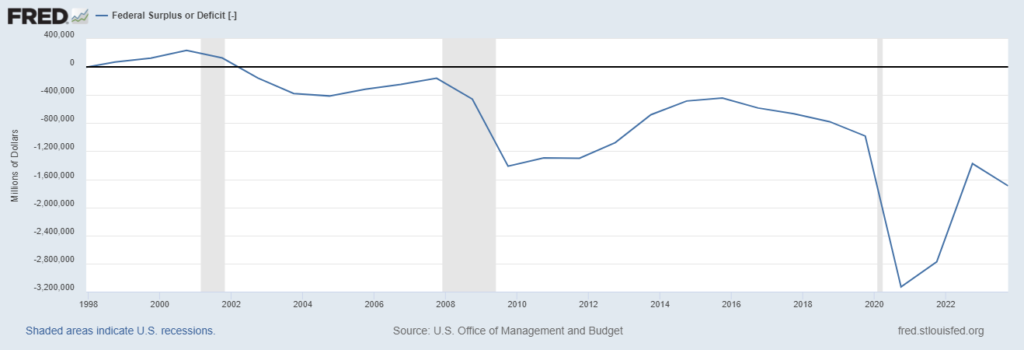

Further, these last 2 administrations of Trump and Biden have increased the federal deficits to levels never seen before. So, even if interest rates did not rise, the federal deficits are still ballooning the federal debt further.

What if interest rates on $35 trillion of debt were to rise, say, another 50% or so in the next 12 months? Well, that would result in quite an increase in the cost just to pay the interest. That would also trigger quite a bit of new demand for the next wave of loans. The beggars… I mean bureaucrats would be out their competing against lots of other governments who also took on massive increases in debt in the last few years… plus everyone else out there in the open market.

Let’s add some perspective to the size of the US government’s debt of $35 trillion.

Consider the size of the debt of the top 100 global debtors: it is under $11 trillion (as in less than 30% the size of the debt of the world’s single largest debtor). Apparently, U.S. companies make up nearly $7 trillion of that $10.8 trillion. Many of the top 25 private debtor corporations are in the banking or financial industry. Others include Toyota, Volkswagen, Verizon, and AT&T.

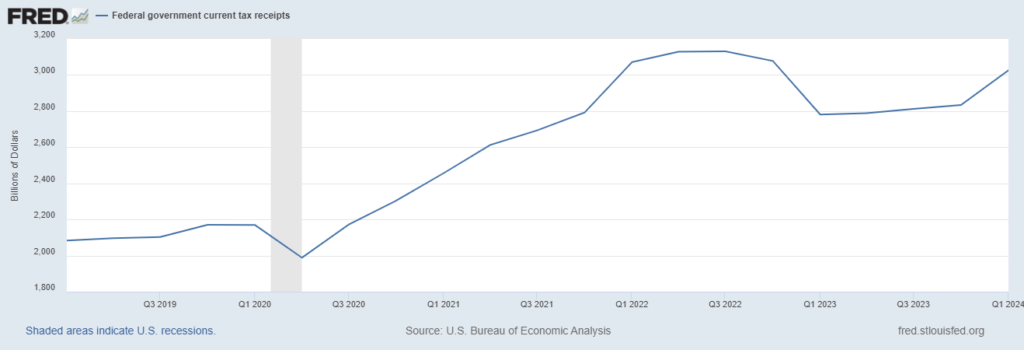

Another way to measure the size of that $35 trillion debt is to consider the size of the US government’s annual revenue. That is below $4.5 trillion. So, hypothetically, if the US government halted ALL spending completely, it potentially could pay off the total debt in less than 10 years…. if only that debt was not collecting any interest.

As a reminder, just to pay interest the cost is $800 billion per year (as in 18% of the revenue) and that is at current interest rates. The US economy as a whole produces about $28 trillion of value per year. The entire world’s economy is valued at a bit over $100 trillion per year.

What is the total of all debt contracts owed in the world? As of late May, the estimate was $315 trillion.

SOURCE: https://www.cnbc.com/video/2024/05/28/how-the-world-got-into-315-trillion-of-debt.html

Governments globally owe about $90 trillion. The debt of the US Treasury is far more than 1/3 of that.

All households on the planet owe about $60 trillion. The US government’s debt is 58% of that.

The US Congress… along with all the other governments and all the other private corporations… are all competing against each other to borrow. How about you and me? If we both go to a lender who only has $45 trillion left to lend, then maybe only one of us will get approved for a loan… and we may have to agree to a rather higher rate to attract that lender away from… every single other borrower available.

Many people may not be clear on what an open market means. Sure, governments occasionally invade other places and seize assets from people and corporations. But even without coercive methods, there is a lot of competition out there for loans.

Banks are paying over 5% for people to lend them money (in CDs). One Credit Union in California is paying 6%.

Why? Why are they offering higher rates than a few years ago?

It’s a competition. If that borrower did not agree to interest rates as high as that, then some other borrower might. Remember, when banks offer a CD, that is the bank trying to borrow from a lender… as in a loan (similar to a short-term bond offered by a government).

Why are there so many corporations offering over 10% on “junk bonds?” Because that is the rate that it takes to attract someone to risk lending them money.

A possible better choice for lending to a government (compared to the US) is Brazil. Their government is offering 11% interest for a 1 year bond. That would be a net gain of about 7% if inflation there remains under 4% (so not far from inflation levels in the US). Plus, Brazil’s government has a total debt that is far below the size of their economy (in contrast to the opposite case in the US).

If you had money to lend… and a lot of it, you would look not only for high rates but for credit-worthy borrowers. The credit of the US Government is something that you might be interested in measuring relative to the competing beggars… I mean borrowers.

Who controls US government policy?

Oops… that topic probably has absolutely nothing to do with any of the other content here. Forget that I mentioned it.

The total debt of the US government is about 150% of what it was 5 years ago. However, the total revenues are up by nearly the same percentage.

It has been more than 20 years since the US government brought in more money than it spent. So, when will that result in soaring interest rates?

I propose it may have already happened. That was in 2020.

Further, all this debt could lead to a frenzied surge in demand for cash… again not a ballooning demand for more loans, but for more cash (for the US government and others) to pay down their debt. Why? What if lenders stop offering loans?

What if lenders say “sorry, your pattern of several decades of losing net worth each year do not appeal to me and I decline to lend to you at any interest rate?” Well then there could be a shift away from borrowing… toward very different behaviors, like rapid selling of assets in order to pay down the prior trillions of debt. Which assets?

Well, Alaska was sold to the US. The Louisiana purchase was a sale to the US by France.

The issue is not so much as which assets will the desperate beggar sell… but which assets are appealing to any prospective buyers (and how appealing). There are other competitions besides the competition for the loans of lenders.

To whom would the US government sell enough assets to cover the $35 trillion of debt principal (plus the promised interest)? Who knows? I do not.

But if that lender intends to pay back the debts plus interest, that could be difficult. If global credit markets shift from enthusiastic lending to conservatism, then even slowly gathering $35 Trillion of cash could be rather challenging.

When there is a shift away from accumulating assets like property to accumulating cash, then the market price of property can plunge rapidly… by 20% or 50% or much more. Or the market value of a currency can decline or simply disappear. On that note, if anyone wants to buy a confederate dollar for a nickel, let me know because I know some collectors who have been trying to sell them for a dime unsuccessfully, so maybe they will be open to accepting only a nickel.